Lucy in Space – A Conversation between Christian Andersson and Filipa Ramos

Filipa Ramos / I feel that you are interested in questioning the notion of evolution, not only in terms of its association with the dominant humanist narrative — largely shaped by Darwinism, its promotion of ideals such as natural selection or the survival of the fittest and its emphasis on the human realm — but also in relation to understanding how it can be displayed in space and in time. This quest for other forms of dealing with that concept seems particularly visible in works such as From Lucy with love (2011), and even in your Self Portrait/Living Fossil (2013).

Is that so? It would be great to know more about your own vision on evolution and how it permeates your work.

Christian Andersson / In the first section of From Lucy with love I put three copies of skulls on display: Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis), a Neanderthal specimen and the Piltdown Man. I made the Piltdown Man skull a part of this trio to add a symbol of a fabricated evolution, the skull being a paleoanthropological hoax in which bone fragments (said to have been collected in Piltdown near Essex, England, in 1912) were presented as the fossilised remains of an early human, a forgery that remained unexposed until 1953.

It's funny that the Neanderthal skull has somewhat changed in status too since I first presented the installation in 2011. The new data that emerged in 2014 concerning cave paintings in Indonesia — now considered to be around 40,000 years old — brought up the question of the possibility of Neanderthals being the creators of the oldest cave paintings on earth, thus questioning whether humans really were the first to make art. After all, the first naturalistic paintings of humans from the Nile River valley in Africa date back around 8,000 years. If humans are responsible for the oldest cave paintings, why does it take almost 30,000 years before we see a similar tradition in imagery picked up again?

I'm not interested in fuelling any conspiracy theories here. What interests me is that we are left to speculations, at least until (if ever) we find solid proof of any of these theories. I like to emphasise this vulnerable state where we have to decide what to believe in, and why. I designed From Lucy with love with this in mind, building a model we don't fully recognize as neither true nor false. I look at it as a source code, consisting of leftover footnotes. I deliberately used a lot of remakes and copies in this system, suggesting that patterns of time and history might also be traced in objects and symbols often overlooked. Let me give you an example: if you cut down a tree and look down at its stump you will have a circular cross-section of years in front of you. However, the multitudes of circumstances embedded in these circles are hidden in this pattern as a memory, presenting a mere graph of the life of this specific tree. To get a wider knowledge of the more recent situation and surrounding events of this tree, the bark might in fact bring a wider insight, even if it's only skin deep. The graph will always be part speculation, while the bark might hold an actual trace. In other words: I like to dig where I stand. You might say that I'm involved in a contemporary archaeology where I use my art to create visual models for possible evolutions and mutations.

In the case of Self Portrait/Living Fossil I'm literally wedging myself into history, merging with one of this planet's oldest and most resilient creatures, the horseshoe crab. Whether I'd really like to learn from this living fossil by carrying its vast carapace as a head or if I hold up this creature as a shield between myself and evolution is up to the viewer to interpret.

Evolution is generally a violent and chaotic process, something that used to shape us beyond our power. If the Piltdown Man is a symbol of a made-up evolution, he now seems like an almost harmless prank compared to many manipulations and alterations being made these days. In many fields we are now creating evolution, not just as a symbolic act but rather as a pragmatic change in the designs of life and intelligence. We don't know yet where this will take us. It's again up to speculation.

FR / There is something in your thought that is very much in tune with the recent revision of the notions of ancestry and definitions of the Modern Human, and its narrative and discourse-based approaches. It was about time to question linearity as the mode for depicting change, and the concept of evolution as a hand that naturally pushes forward the so-called progress of humanity!

Understanding early humans requires dealing with a far wider — and more complex — scenario, in which the history of mankind is entwined with that of other species, it's murky and it's certainly not based on a Eurocentric geography. These issues seem to be at the heart of your thoughts, as an essential part of some of your works.

In this sense, the recent discovery of various Neanderthal cave etchings and stencils in the south of Spain and in Gibraltar demands the re-evaluation of the Neanderthals — unfairly portrayed in popular culture as the brute, violent caveman from the Ice Age — thus opening the door for another possible version of the story of the "survival of the fittest" that we've been told. Perhaps "fittest" does not mean "finest" but actually "brutest"? And perhaps the "brutest" was not the Neanderthal after all?

At the same time, we're witnessing the re-evaluation of the dating of important cave artistic manifestations that demolishes the foundations of the canon of Western, European art, as it happened with the drawings of wild pigs and stencilled hands in the caves of Maros in the south-western side of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, which are now considered to be 39,900 years old (the great-grandmothers of Lascaux, which are only 17,300 years old)!

Incredibly, it was also in Sulawesi that the female crested black macaque took a series of selfies that became world-famous! It raised a long dispute on copyright issues between the owner of the stolen camera and Wikipedia, which assumed that the legal owner of the rights to the images was the macaque and not the detainer of the camera. Sulawesi certainly is the site where the borders between human and non-human animals are being erased and redrafted!

But back to us. Where do you stand, as an artist and as a man, in relation to these current revisions? In what way do you think that what you're presenting has an impact in these reconsiderations of the narratives of (pre)history and on the reshaping of the figure of the Modern Human?

CA / At the time I received your question I was just checking when the Chauvet Pont d'Arc cave replica project would open to the public, a site I'm looking forward to visiting more than anything at the moment. It seems that in April this year we'll have the chance to experience the 8.000 m2 cave replica and educational complex based on the original Chauvet Pont d'Arc cave, containing some of the most well-preserved cave drawings and paintings ever found. The original cave is interesting for multiple reasons, but in the light of our discussion one specific detail may be worth mentioning: the radiocarbon tests suggest that there were two periods of creation in the cave, the first around 35,000 years ago and the second 30,000 years ago.

What we are looking at is something that in a modern time span is almost impossible to grasp: a multi-layered piece of artistic craft separated by some 5,000 years. What would seem to us like a single "image" consists in fact of two widely separated realms, which might even have been made by two separate species. What if the sections dating back 35,000 years were created by Neanderthal hands, and the later ones made by human beings? This is not a widely supported theory, and that's my point here. I'm free to speculate about this, to open myself to this possibility, and maybe I'm getting close to answering your question: I have no idea of how my practice has an impact on these questions whatsoever, and I don't really have the intention to direct or redirect anyone into a fixed position of believing in this or that. My aim is to share imprints of my thoughts that might introduce the viewer to a more multi-layered perception of the world.

FR / There is, indeed, something extremely appealing but also very dark in this possible scenario of the fate of the artistic Neanderthal: if we have a glimpse of another species' creative expressions we also foresee the shaping of the human as a natural-born dominator, from his very inception as a being. It's both exciting and very sad.

In relation to your desire to share your multi-layered visions of the world, is there a process, a method that characterises such an approach and that can be observed in your practice?

CA / My general mistrust in a large part of the Eurocentric narrative of (pre)history becomes quite clear when you look at some of the references I've used in my practice. Maybe it's most clearly present in my installation Paper Clip (The Baghdad Batteries) (2009), where I openly suggest an alternative source (and place of origin) of a well-known European invention, the galvanic cell (Alessandro Volta is credited for the invention of the first electrical battery in 1799). Again I'm not claiming that the Mesopotamian vessels found were ever used as batteries, I'm simply reproducing a myth, giving it a purpose (in this case charging an electric magnet, which in itself is one of the cornerstones in electrical and mechanical evolution throughout western industrialisation, as a relay and later on as a central part in transmitting devices such as Morse code machines etc.). By doing this I might in thought open up an alternative evolutionary path, where galvanic cells and possibly electromagnetism existed in the Middle East around, let's say, 100 BC. My installation was not made to function as a pseudoarchaeological proof, it's designed to be a challenge for European minds.

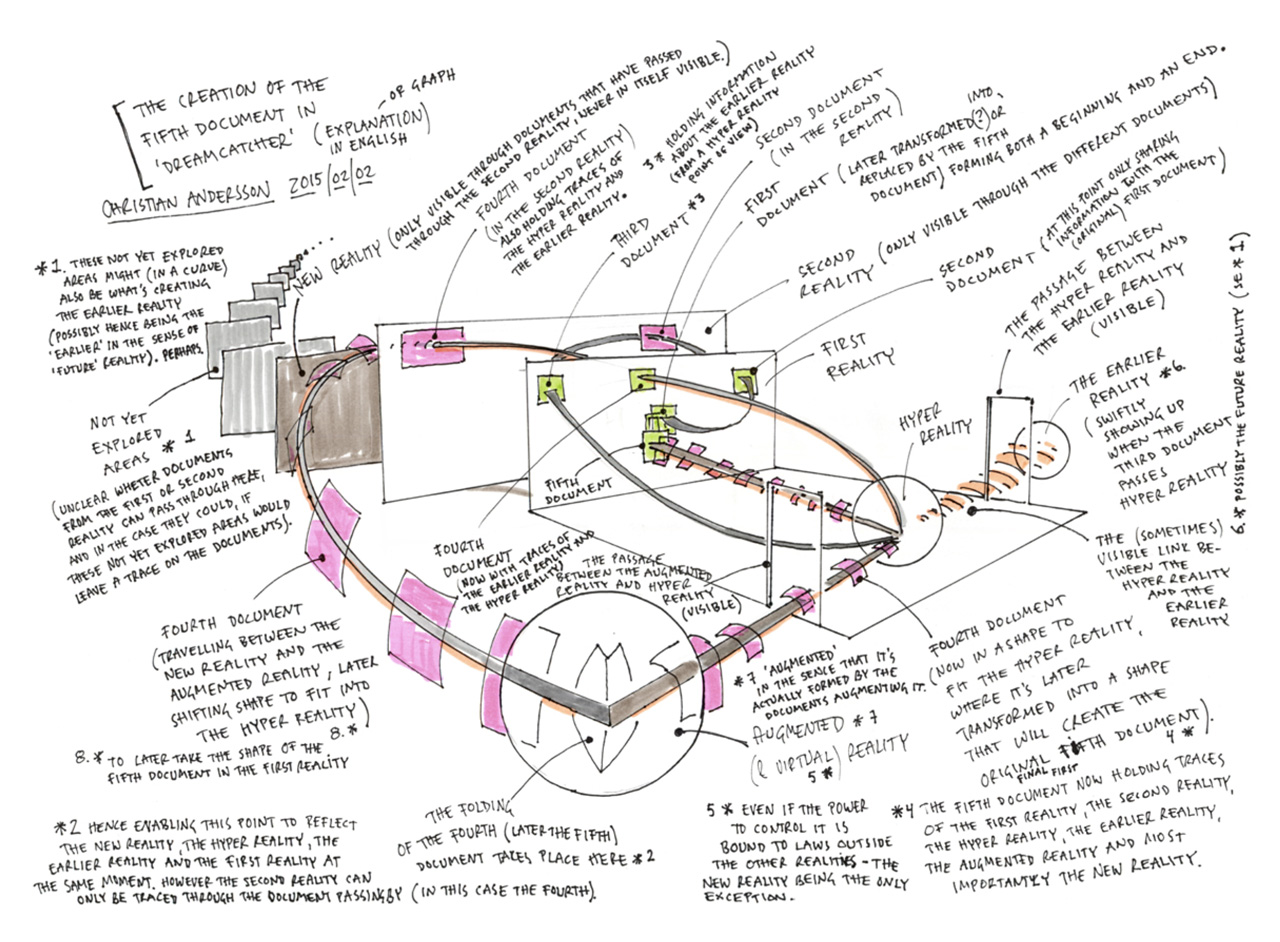

I'm constantly training myself in looking at things from multiple angles at the same time, as a kind of brain workout. I'll give you an example: in the image below I try to explain the different strata or dimensions a "document" is passing through in my latest video Dreamcatcher (2015). This drawing might seem like pure absurdity, which it may very well be, but it's also just like practicing your eye and hand by drawing a still life. I'm trying to follow an idea where notions of reality and imagination do not oppose each other, where the point is to reach a different set of logics, based on reflecting on facts and events in a wider sense.

This notion is something I'm trying to communicate through what I do, and I often relate to my works as antennae, steadily and patiently transmitting a code embedded into their structure. All cultural languages sooner or later become a sign of their time, and that is as important as it is inevitable, because this means they might later serve as a reference point when observing the changes of the world.

FR / This scheme presents a big challenge to the viewer: text and image compete with one another, the image occupying the central place of the surface while the text is surrounding it and imposing what appears to be meaningful and useful information to it, but it might well be just a set of instructions for the correct functioning of this weird dispositif. There is, however, a sense of a chain-production process in progress in which all those documents that travel one after the other, in a sequence, traverse various reality gates. Can you explain what the Dreamcatcher is?

CA / In Dreamcatcher we're observing the recording of a dream, in my fantasy a dream inside the mind of an artificial intelligence. One major inspiration when developing this work was a painting by Giorgio de Chirico, Le cerveau de l'enfant (1914) that I experienced at a young age at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. I wanted to create a piece with a similar metaphysical ambiance of lucid dreaming like the one in de Chirico's image, where the main story seems to occur beyond the actual picture, behind the closed eyes of the figure in the painting. For me, Dreamcatcher really is the next evolutionary step for From Lucy with love, where the information, now in the shape of images, has melted down into a two-dimensional landscape, just as in From Lucy with love we can observe collected phenomena and artefacts, but this time we are not in control of the observation. We are led over this landscape by a seemingly conscious eye, scanning the surface, possibly looking for a refuge, maybe even searching for a dimension beyond the surface. Unlike the pre-assembled structure of information in Lucy, the information in Dreamcatcher is assembling itself into a field, a mindscape, where the landscape and the mind become the same entity, a multiverse protagonist gradually freeing itself from its programming.

For me the work is not a fictional story per se. I'm merely using a visual framework to illustrate a possible scenario. Dreamcatcher is a sketch, designed to fully unfold in a future when ideas and events have caught up with it. Of course I can't be sure that this will ever occur, but that is nevertheless what it's designed for. The point for me here is to use imagery to convey the feeling of a deeper future insight yet to be experienced. This is tricky, partly because it also involves myself, since I don't fully understand this either. I simply share my confusion with the viewer, proposing a couple of guidelines that one day might lead to a wider understanding of this visual entity, and the material it is entwined with.

FR / It's a fascinating position. You don't seem as interested in questioning the actual validity of something that is generally taken for granted as you are in drafting new explanations, which open totally new narratives, and by doing so, you are disclosing the lack of any separation between speculative questioning and scientific research. Science is fiction?

CA / I'm choosing to hold on to that notion, because it helps me stay observant in my research, but I'm not saying that this is the general case. What I am saying is that it very much seems to depend on the framework: read about the multiverse in a sci-fi novel and it's fiction. Read about it in Scientific American and it's considered science. To me the distinctions hardly matter, as I conceive it all to be part of an ongoing story wherein some parts will, depending on the times, be considered fantasies or fiction, while others are read as science, facts.

The question is why we seem so desperate to separate these two positions. Maybe because it's closely related to the definition(s) of reality. Fiction can serve as a buffer zone towards reality, which is very useful if you want to draw a clear line between what is promoted as real and what is labelled as fantasy. Editing the concept of reality is of course not a new phenomenon, as throughout history the concept of reality has been actively modified, as a tool to retain the ruling power of that particular time. If you're in a position of power, you can make the devil a real creature while claiming that ideas about the earth being a sphere are a dangerous figment of imagination etc. It's easy to laugh at examples like these today, but it's also fairly ignorant to be confident in the fact that we would never be subjected to manipulated definitions of reality today. To discard information as fiction or fantasy is still a very effective way of ridiculing (or threatening) whoever promotes a subversive point of view. I'm not picking up the tin foil hat here, claiming that an Illuminati power is keeping us in the dark. I'm simply saying that fiction might be more real (and useful) than we think.

This is why science fiction writing throughout history has interested me, since it effectively makes use of the field in between reality and fiction. By using fiction to camouflage reality, the message can be left biding its time, slowly seeping through.

In the light of these ideas and fascinations, I guess it's not surprising that the exhibition at Kunstmuseum Thun follows this in-between attitude. The mutated objects and events exhibited could be seen as drafts for some kind of future, where these bodies have evolved into a new configuration, asking for updated readings and interpretations. Maybe it's even less surprising that my main new work for this exhibition carries an air of science fiction, with a dreamscape as its main structure. In times where we are constantly monitored and watched over, dreams might be our last sanctuary not subdued to surveillance, where we can roam freely and experience the limitlessness, mainly because we are not in control of them. It might be about time we start thinking of letting go of obsolete ideas of control and patterns, as pattern recognition might be an inadequate method when defining the world today. Perhaps instead we have to be prepared for scenarios where history doesn't repeat itself and where everything isn't moving in cycles or according to the graphs. The world is rudderless, and just like our dreams it still remains a mystery.

Malmö/London, late winter 2015

The interview was first published in the exhibition catalogue Legende, Verlag für moderne Kunst, Kunstmuseum Thun (2015).